On Thunderstorms & Emotion

While I haven’t yet written a post on thunderstorms and emotions, there is one on clouds and emotions. They are not the same. However, I can refer back to the story I told within that first post in order to paint a better picture for this one.

When you were a child playing on the soccer field with your child buddies and saw a cloud in the distance that was spitting lightning, you may have notified the coach (who should have been paying attention) and let them know there was a looming danger. That’s anxiety.

When that same cloud moves over your soccer field and all of you are safe inside the park’s communal restroom (where it stinks), that same lightning carries with it booming thunder that crashes all around you and makes it impossible to talk to one another. Then the rain falls, usually in buckets, and the noise on the tin roof of the restroom drowns out even the thunder. Here you might be excited.

Then, far off in the distance, you hear the warble of a tornado warning. Suddenly the torrential rainfall that’s above you is not nearly so exciting. You are now frightened, hoping that tornado doesn’t fall from the sky and take out the restroom in which you and your buddies thought you were safe.

When the rains let up and the thunderstorm moves on, you step outside. Here you may be relaxed, but at the same time jittery. You may think another storm is coming, and that’s probably right. Your heart may be racing, your palms sweaty and even though you joke with those around you, in reality, you all are thankful you are still alive.

The coach’s car has been flipped over, however, and that both surprises you and fills you with a sense of awe at the raw power contained in a single storm.

Naturally here, I was referring to the thunderstorm, that way nature attempts to restore balance to an unstable atmosphere.

What’s that you say? Restore balance? Unstable atmosphere? Yes!

The way nature uses thunderstorms to restore balance to an unstable atmosphere is akin to the way a plot is intended to resolve a conflict. You can also use the stages of a thunderstorm to develop your plot.

When I ran my experiment on weather and emotions, I did not specifically call out thunderstorms. Rather, I decided to group them in with extreme weather.

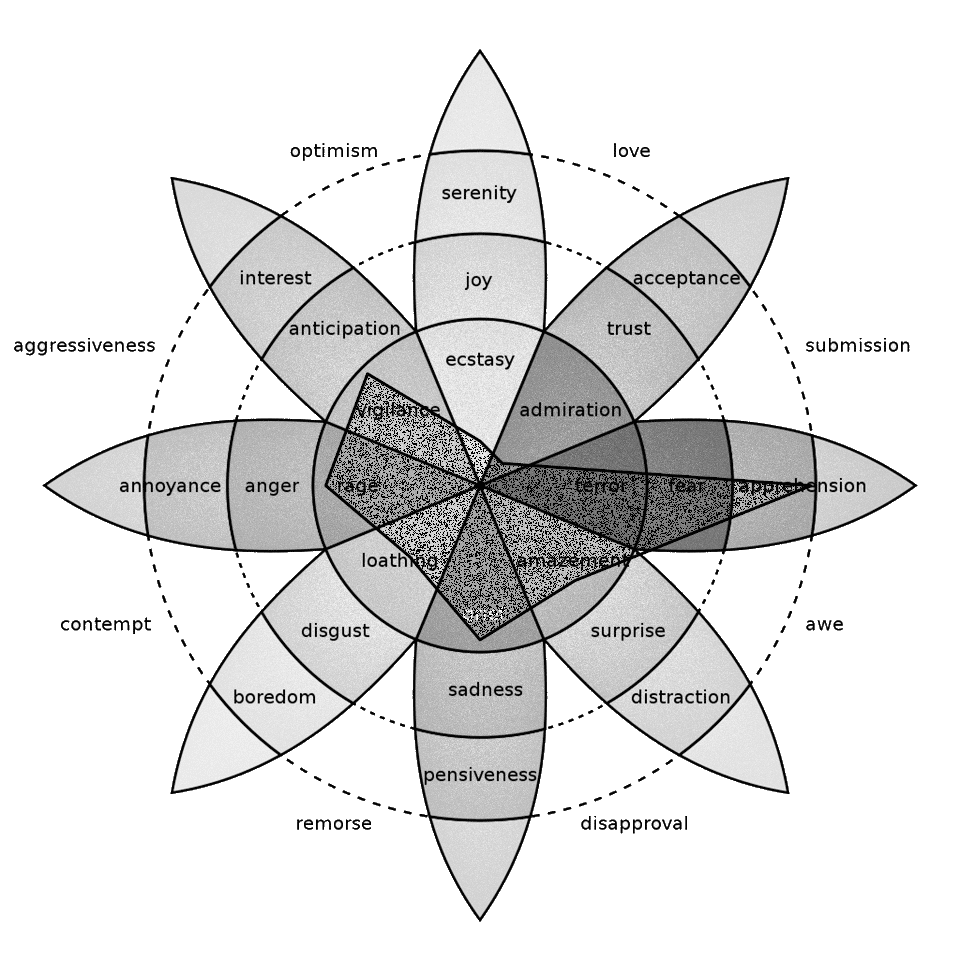

The below radar graph superimposed on Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, shows how participants in the survey responded to images of extreme weather (most of which were, in fact, thunderstorms).

As you might expect, the emotions most associated with thunderstorms (extreme weather) were terror, fear and apprehension. Vigilance and a little rage came in second. There was also a little sadness.

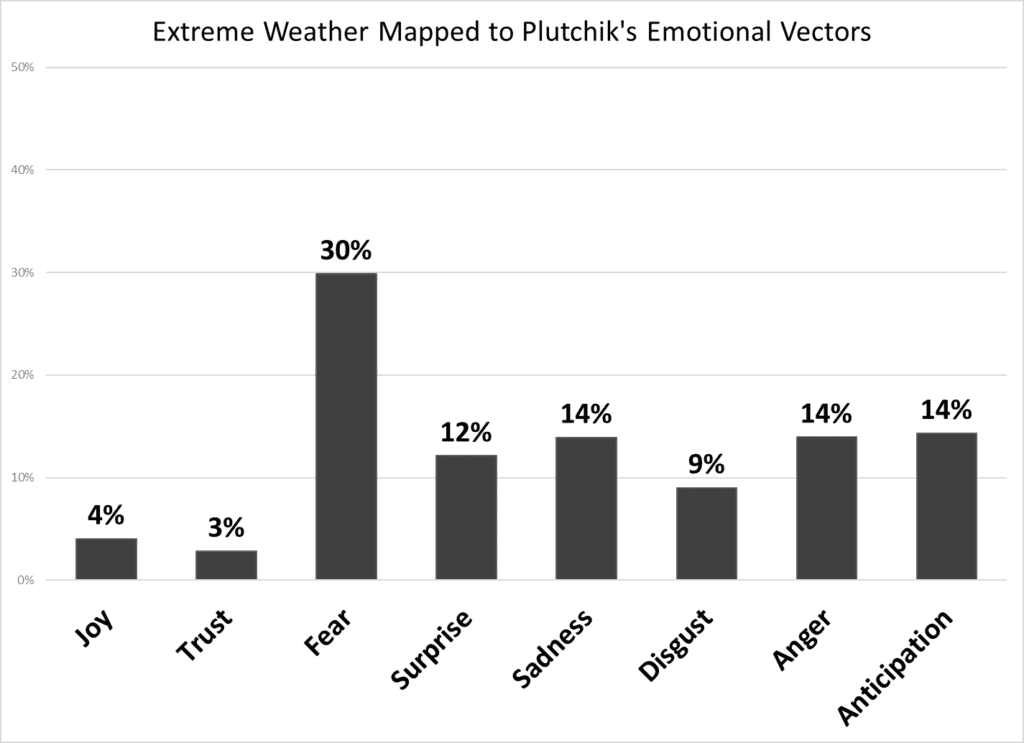

Here’s a better look at the distribution of emotions.

What does this tell us? Thunderstorms within the narrative can increase those particular emotions or at least mirror those emotions that are present in the characters.

We know this. Thunderstorms are often used for effect.

Here are a few literary examples:

The thunderstorm in King Lear by William Shakespeare mirrors his own descent into madness. That madness triggers terror in others as well as apprehension.

LEAR

King Lear, Act 3, scene 2

Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drenched our steeples, drowned the cocks.

You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head. And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world.

Crack nature’s molds, all germens spill at once

That makes ingrateful man.

A thunderstorm in the short story “The Storm” by Kate Chopin (1898) rages on as two lovers act on their desires. It is the comforting of the fear that Calixta has which prompts this act.

“Calixta,” he said, “don’t be frightened. Nothing can happen. The house is too low to be struck, with so many tall trees standing about. There! aren’t you going to be quiet? say, aren’t you?” He pushed her hair back from her face that was warm and steaming. Her lips were as red and moist as pomegranate seed. Her white neck and a glimpse of her full, firm bosom disturbed him powerfully. As she glanced up at him the fear in her liquid blue eyes had given place to a drowsy gleam that unconsciously betrayed a sensuous desire. He looked down into her eyes and there was nothing for him to do but to gather her lips in a kiss. It reminded him of Assumption.

“The Storm” by Kate Chopin (1898)

We can’t ignore Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. Storms are all over the book. When a storm rages the night Heathcliff runs away, Nelly narrates:

“About midnight, while we still sat up, the storm came rattling over the Heights in full fury. There was a violent wind, as well as thunder, and either one or the other split a tree off at the corner of the building: a huge bough fell across the roof, and knocked down a portion of the east chimney-stack, sending a clatter of stones and soot into the kitchen-fire.”

From Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847)

It’s hard not to see the fear, terror, apprehension, awe, and even submission in that example.

And now the Science!

When using thunderstorms in your narrative, pay attention to the proper development (er, the meteorology of your book).

Thunderstorms can be broken down into 3 stages.

In the Cumulus Stage, you see the happy cloud. Moisture and air is drawn up toward what’s called the “convective condensation level” where clouds form. If there is enough instability in the air, the parcels continue to rise, the moisture continues to condense, and the clouds get bigger.

During the Mature Stage, what goes up, must come down. The rising air has pushed our happy cloud to the limit and it peeks above the freezing level. As ice crystals high within the cloud flow up and down in the turbulent air, they crash into each other. Small negatively charged electrons are knocked off some ice and added to other ice as they crash past each other, separating the positive and negative charges of the clouds. When the top of the cloud becomes positively charged and the base of the cloud becomes negatively charged–boom–lightning flashes. Moisture droplets merge and form hail which is then sucked up and down within the cloud. As the hail falls below the freezing level, it melts and rain falls.

More stuff happens, and tornados come.

Finally, when all the downward motions overtakes the upward motion, the thunderstorm moves into the Dissipating Stage. Rain continues to fall, the cloud falls apart, and it’s pretty much over.

In order for all of this to happen, three elements are needed:

- moisture

- instability, and

- a lifting mechanism

One way to create instability is to place cold air (which sinks because it’s heavy) over warm air (which rises because it’s lighter). The cold over warm creates an atmospheric COW. Because the atmosphere is always trying to maintain a certain equilibrium, violent things must happen.

That is what I mean when I said earlier that thunderstorms are nature’s attempts to restore balance to an unstable atmosphere.

It’s that instability you want to use in your fiction. Most likely, you already have it: your conflict.

Learn more in Creating Atmosphere with Atmosphere: How to Use Weather as a Literary Device