On Fog & Emotion

I was in 4th grade when I read the poem “Fog” by Carl Sandburg. For those who don’t know it:

The fog comes

on little cat feet.It sits looking

– Carl Sandburg, “Fog”, 1916

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.

This was my first exposure to how much weather can impact literature. Mind you, in fourth grade I was not thinking about using weather as a literary device but instead what I was going to do at recess. I want to say it probably rained that day I read the poem in class, but as I was in Phoenix at the time, that’s doubtful. It was probably blisteringly hot, unless it was winter. Then it was only warm.

What images come to mind when you read Sandburg’s poem? For me, who lived with a cat, I connected with the first line in ways that were intended: my cat would frequently come into my bedroom on his little cat feet. One moment I would be alone, the next looking at a cat.

Like that cat (named Friday, by the way), fog does not announce itself very well. It’s stealthy, serene at times, and so often shows its face early in the morning when the coffee still hasn’t brewed.

Merriam-Webster defines this weather phenomenon as a “vapor condensed to fine particles of water suspended in the lower atmosphere that differs from cloud only in being near the ground.” Second to that would be “a state of confusion or bewilderment.” There are other definitions, but I’ll stick with these two for the purposes of this article.

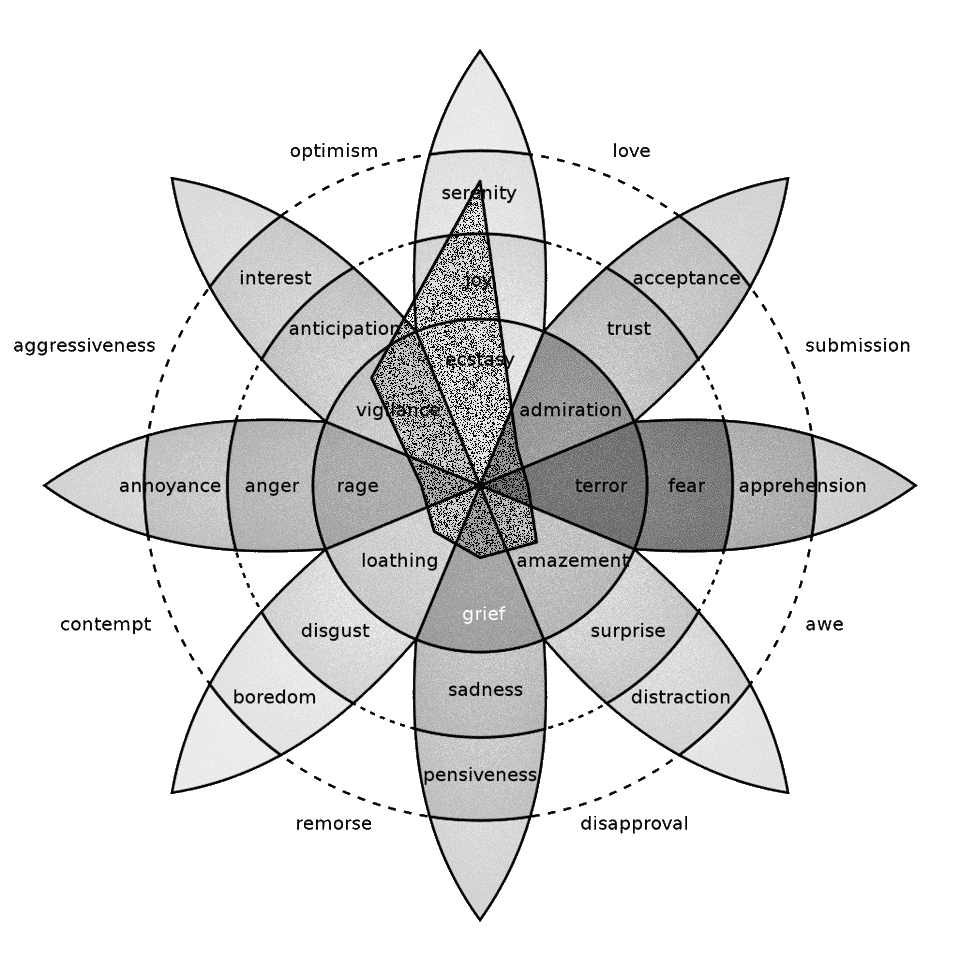

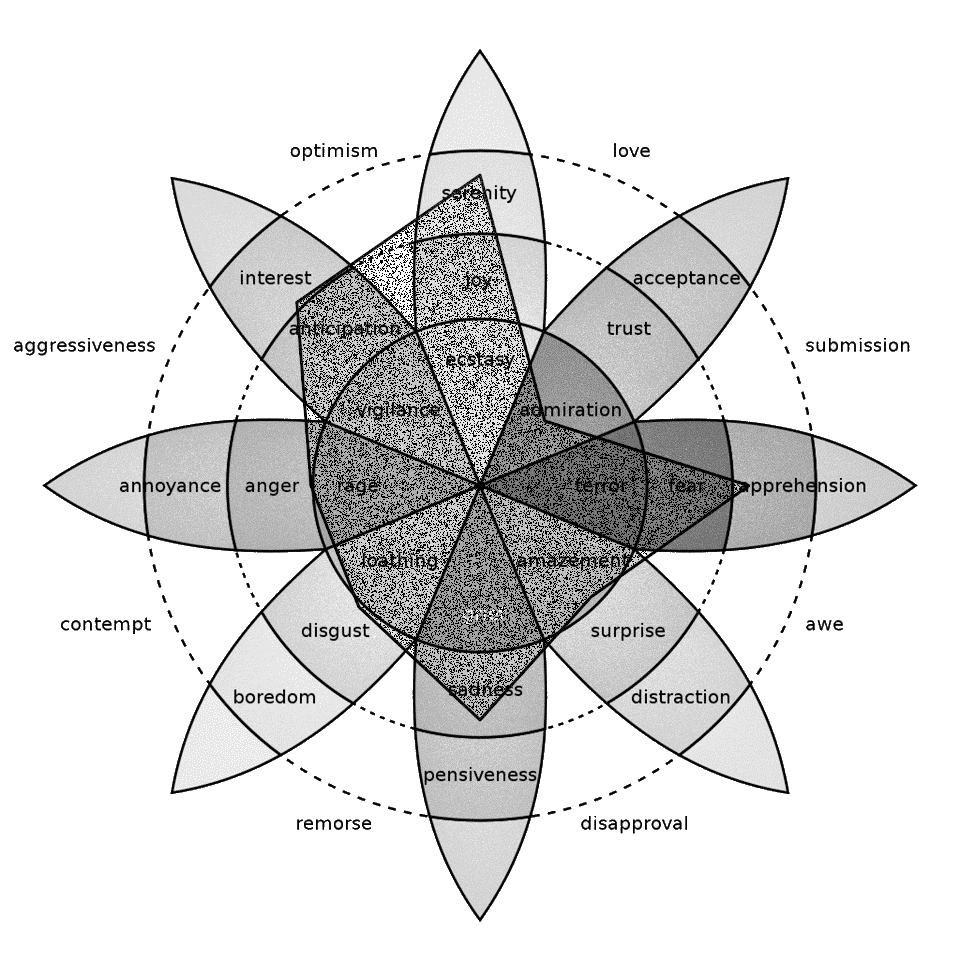

First off, fog is essentially a cloud near the ground. Recalling my experiment with weather and emotions, clouds typically conjure up feelings of serenity or joy, provided they are high in the sky and not angry (stormy). The below radar graph superimposed on Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, proves this. (For more information about the study I conducted, see A Little Experiment with Weather and Emotions.)

When on the ground, however, those feelings are morphed a little. It’s still a cloud, but the emotions are definitely more diverse.

Here you can see that while respondents still selected emotions along the spectrum of Joy (ecstasy, serenity, optimism and love), there is an equal push toward both the spectrums of Anticipation (vigilance, interest, aggressiveness and optimism) as well as Fear (terror, apprehension, submission and awe). So it’s not all happy clouds on the ground for many people.

Take a look at the following image and tell me what you feel?

For me, I see this as an idyllic scene, one wet yet mysterious, open to the possibilities of whatever is out there just over those hills. For you, this may conjure emotions that are vastly different. Stick a colorful flower right there in the middle of that first hill and what comes up? Hope, maybe. Optimism.

That’s the beauty of using weather as a literary device. While there are a diverse feelings that may come up when describing a certain weather event in your stories, there is a pattern to what the reader will feel. Very few of my nearly 600 respondents said that fog conjured emotions along the spectrum of Trust, Rage, or Amazement.

So if you’re looking to guide the reader toward a particular emotion in your scene setting, you can use fog in a few different ways. We’ve seen this in movies, and we’ve felt this reading certain books.

It can be the blurring line between illusion/dreams and reality or it can portend uncertainty and mystery. Like Merriam-Webster’s second definition, it can also be synonymous with confusion, like a wandering loner in your story stumbling through the fog unsure of who or where he is.

That same loner might be depressed, but look at the chart above. While sadness is certainly indicated as a response to images of fog, it is not primary.

Think about it this way: without fog in our stories, you’d lose a lot of 19th century literature from Doyle to Dickens.

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ‘prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.

–Charles Dickens, Bleak House, 1853

Fog may come in on little cat feet, but look at what it can do to your reader’s state of mind.

Learn more in Creating Atmosphere with Atmosphere: How to Use Weather as a Literary Device