What is Solar Weather?

When I was a younger lad, I had an opportunity to shift my airfield weather focus to something a little more “out there”–solar weather observation and forecasting. What kept me from joining those illustrious ranks of others who had gone before was this: everyone else wanted that job, too.

It was in Australia, mate.

Talk about your adventure. As I said, I didn’t get the job, but that didn’t damper my attitude toward solar weather. After all, the fact that we have weather in the first place–and the fact that we exist at all–is because of that big ball of gas in the sky.

Solar weather may not be the best term to use, though. The field studies the composition of the sun, its gaseous atmosphere, and the impact of sun storms on our own planet, our lives, and our technology. The “official” term is space weather, a branch of heliophysics, which sounds so much cooler than solar weather. I mean, why not call it geo-solar-impactfulness?

Space weather is all about the interaction of the sun and the Earth. Earth’s atmosphere is made of several layers, each of which is affected by the sun: the troposphere (where we live), the stratosphere, the mesosphere, the thermosphere (where the ionosphere and magnetosphere begin), and the exosphere.

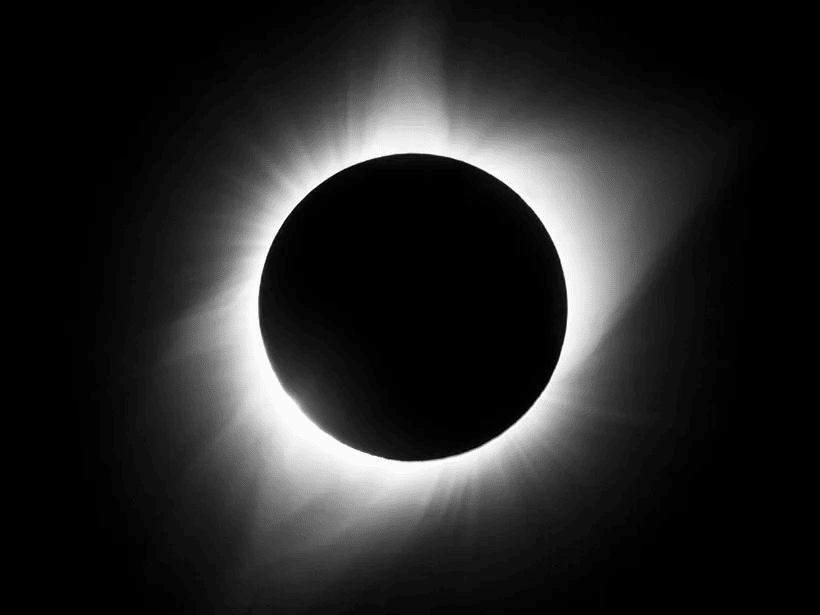

The sun is a nice ball of hot plasma, heated by nuclear fusion which coverts hydrogen to helium and matter into energy. That energy travels across the solar system, eventually impacting the planets. When the moon covers the sun, we can see the sun’s own atmosphere: the chromosphere, the transition region, the corona and the heliosphere.

There’s a lot out there on the composition of the sun, its dynamics, and a bunch of formulas that I don’t understand. What I do understand is how the sun can play a part in writing, not only as an obvious source of light, but also as a literary device all its own. It’s interplay with the Earth can drive plots.

The sun can do some real damage to our own little part of the universe. It can also give us some awe-inspiring celestial displays which, when used effectively, can enhance the narrative of our writing.

Aurorae

We’ll start with the awe-inspiring stuff. Romantics (at least in the northern hemisphere) may call them the “Northern Lights” but the official term is aurora borealis. In the southern hemisphere, the same celestial feature is known as aurora australis or “Southern Lights.”

The sun is continually spitting out charged particles from its corona and creating a solar wind. When the solar wind slams into our ionosphere, auroras appear.

While it was Galileo who coined the term aurora, the first recorded viewing was some 30,000 years ago (in a cave painting). Humans have been continually fascinated with these lights for thousands of years.

In 1873, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a decent description of an aurora.

And now the Northern Lights begin to burn, faintly at first, like sunbeams playing in the waters of the blue sea. Then a soft crimson glow tinges the heavens. There is a blush on the cheek of night. The colors come and go; and change from crimson to gold, from gold to crimson. The snow is stained with rosy light. Twofold from the zenith, east and west, flames a fiery sword; and a broad band passes athwart the heavens, like a summer sunset. Soft purple clouds come sailing over the sky, and through their vapory folds the winking stars shine white as silver.

–H.W. Longfellow, The poetical works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1873)

To use descriptions of auroras in your writing is to invite awe in the reader. Literature and mythology is filled with fascinating stories and poems about these lights.

The lights can also be anthropomorphized. Herman Melville personified the advance and retreat of the Northern Lights like that of an army. Or perhaps, the end of the Civil War prompted Melville to use the Northern Lights as allegory (the poem was written in May of 1865).

What power disbands the Northern Lights

After their steely play?

The lonely watcher feels an awe

Of Nature’s sway,

As when appearing,

He marked their flashed uprearing

In the cold gloom–

Retreatings and advancings,

(Like dallyings of doom),

Transitions and enhancings,

And bloody ray.The phantom-host has faded quite,

–Herman Melville, Aurora-Borealis: Commemorative of the Dissolution of Armies at the Peace (1865)

Splendor and Terror gone–

Portent or promise–and gives way

To pale, meek Dawn;

The coming, going,

Alike in wonder showing–

Alike the God,

Decreeing and commanding

The million blades that glowed,

The muster and disbanding–

Midnight and Morn

Keep in mind, however, that unless you’re setting your story in higher latitudes, auroras will typically not be visible. However, in 1989, the Northern Lights could be seen as far south as Honduras during a solar storm which temporarily knocked out electricity across all of Quebec.

Consider this as a story idea: what if the Aztecs witnessed a similar event? How would they respond? It may not have been with awe at the sight, but perhaps unbridled fear that their gods were angry.

The Carrington Event

Of course, pretty lights in the sky is not all that the sun is capable of producing. There is a flipside to all this.

In 1859, a geomagnetic story was recorded by Richard Carrington and Richard Hodgson. The event has since been viewed as the strongest ever recorded and would be considered at the top range of NOAA’s space weather scales.

The aurora was seen as far south as Mexico. In my neck of the woods, the Northern Lights were bright enough to wake miners who went about their morning business clueless to the time. Telegraph operators found they were able to send and receive messages without being connected to a power supply.

As a Baltimore newspaper noted: “the quiet streets of the city resting under this strange light, presented a beautiful as well as singular appearance.”

Imagine if that same event happened now. Blackouts and damages to electrical grids would cause mass panic, and according to Lloyd’s of London, the estimated cost of such an event in the U.S. along would be upwards of $2.9 trillion.

Perhaps Aristotle figured out that bad things could happen with the aurora. In Meteorologica, a horribly wrong book about all things weather that only gets one or two things right, Aristotle writes:

For we have seen that the upper air condenses into an inflammable condition and that the combustion sometimes takes on the appearance of a burning flame, sometimes that of moving torches and stars. So it is not surprising that this same air when condensing should assume a variety of colours. For a weak light shining through a dense air, and the air when it acts as a mirror, will cause all kinds of colours to appear, but especially crimson and purple. For these colours generally appear when fire-colour and white are combined by superposition.

–Aristotle, Meteorologica I:v

Yes…maybe the sky is on fire.

Learn more in Creating Atmosphere with Atmosphere: How to Use Weather as a Literary Device